Natural Resources Research & Management

Natural Resources Research & Management

A closer look at Ichauway’s first wildlife data visualization.

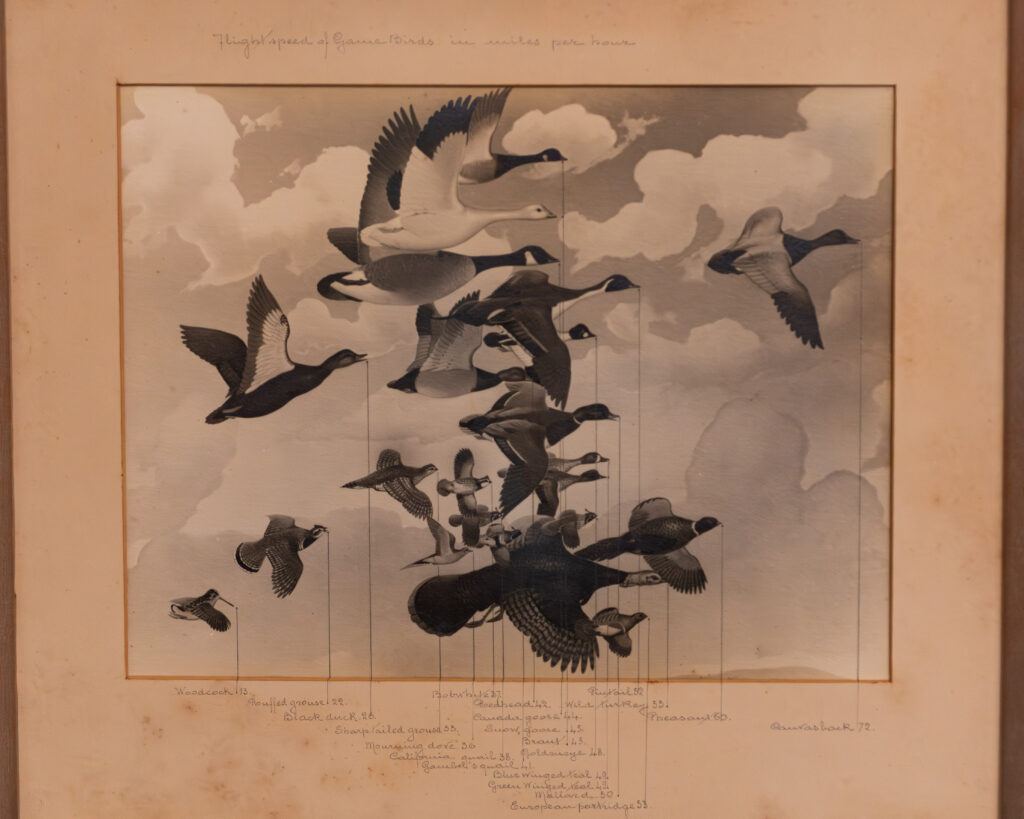

From the American Woodcock at a paltry 13 miles per hour to the blazing Canvasback at 72 miles per hour, Athos Menaboni’s 1941 piece entitled Gamebirds in Flight represents a midcentury version of the near ubiquitous data visualizations we encounter daily in our digital lives.

The original painting is front and center in the living room of the Woodruff House on the grounds of The Jones Center at Ichauway, perched on a bluff beside the Ichawaynochaway Creek. The Woodruff House, named for the late Robert Woodruff, longtime leader of the Coca-Cola Company from 1923 to 1980, was built in 1931. Over the years, when Woodruff would escape the bustle of Atlanta to his home on Ichauway, he hosted hundreds, if not thousands, of business and personal guests. So many eyes have gazed upon this painting, and it has undoubtedly sparked lively conversations.

Mr. Woodruff had a longstanding relationship with Menaboni, commissioning him annually from 1941 to 1984 to paint his annual Christmas cards. All but two cards were adorned with Southeastern avians found on the Ichauway property. This particular piece caught my attention because, unlike most of Menaboni’s works that depict a single species, this one contains 22 species flying in an unnatural manner. Upstairs in one of the house’s five bedrooms, hangs a smaller, annotated version of the painting with each species’ flight speed in miles per hour below every bird.

This got me thinking: who did Menaboni consult for these flight speeds, and would these speeds hold today with modern technology and observations? Does the painting reflect the maximum flight speed or the average speed? For upland species, do we assume the bird is cruising or flushed? For the migratory waterfowl, do we assume near-ground speed, or peak migration speeds at higher altitudes? These many factors and nuances set the stage for a fun investigation.

A quick Google search rendered no such image of the painting, another mystery as the works of Menaboni are widely circulated. Was this piece a special commission by Woodruff himself? Who decided the ultimate or relative flight speeds? I imagine a heated, yet friendly fire-side debate in the Woodruff House amongst sportsmen with lowballs of Scotch after a long day of wing shooting at Ichauway. I personally would like to have witnessed the discussion that spawned the artwork.

Here’s a roundup of some of the anecdotal and, in some cases, scientific measurements for many of the 22 depicted gamebirds from the slowest to the swiftest:

![Photo of a blue-winged teal in flight with text that reads [Despite being characterized as a fast duck by many waterfowl hunters, teal are some of the slowest ducks in North America].](https://www.jonesctr.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/usfws-blue-winged-teal-flight-large_text.jpg)

The 72-mph record for the fastest duck in the world by a Canvasback was eclipsed substantially by a Red-Breasted Merganser clocking in at 100 mph while being pursued by an airplane. More recently, a drake Mallard was clocked at 103 mph in April 2024 during migration by the Cohen Wildlife Lab of Tennessee Tech University. The little guy had help from the atmosphere, after all; tail winds are notorious for increasing migration speeds. Regardless, the speed is quite impressive.

Overall, the painting depictions are decently accurate, particularly considering this work predated wildlife acoustic telemetry studies, which began in 1956, and GPS tracking that began in the 1900s. Final verdict: an oldie, but a goodie. Cheers to you Mr. Menaboni, your art continues to ignite discussion and appreciation for the natural world.

Article by Rachel McGuire, Education & Outreach Coordinator of The Jones Center at Ichauway.

Special thanks to Russell Clayton and the Troup County Archives for their consultation and photographic contributions.